The Kamenz-Herrental concentration camp subcamp during the Nazi era – structure and operation

Conditions in the camp

The goal of 'extermination through labor' was enforced in the camp. Daily life, from early morning until night, was marked by suffering: constant physical and psychological strain, inadequate hygiene, constant hunger, fear of the ever-present death of fellow prisoners, and the brutality of the guards.

The camp was guarded by 24 SS soldiers. Prisoners were beaten by SS men and kapos (inmate functionaries who, on behalf of the SS and in exchange for privileges, supervised other prisoners) wherever possible. The blows with rubber truncheons, as already during the transports, were mainly aimed at the head. Guards would whip prisoners even for the slightest reason.

Camp leader Wirker

Most witnesses, whether former prisoners or local residents, emphasized that Wirker was particularly brutal.

One day a prisoner lowered himself from an upper floor down onto the roof using a blanket and managed to escape. After a farmer near Riesa recaptured him and returned him to the camp, he was beaten by the guards. The following day he went to work with a bandage around his head, and one day later he was no longer seen – had he died? Wirker gave no explanation, saying: 'One should have no pity with such people.“

During air raids, Wirker walked around the factory building with a loaded pistol and fired at prisoners who appeared at the windows. Gunshots were often heard in the camp, sometimes followed by human moaning. No killings were actually witnessed, but in one case Wirker was heard threatening a prisoner: 'If you were not from Chemnitz, I would shoot you!

Supply

As the number of prisoners increased, the cooking kettles became completely insufficient, which was reflected in the extremely poor nutrition: there was almost only turnip soup, and never enough of it. After meals, prisoners rushed to the waste heaps at the glassworks searching for anything edible, such as potato peels. Guards beat them there and kicked them; sometimes a prisoner remained lying motionless.

The first cook, a Pole, had stolen food and then escaped with other prisoners through the drainage channel from the camp. It is unknown whether the escape succeeded, but afterwards the remaining prisoners were beaten all the more severely, and some died from it.

However, the poor food situation could not be concealed from the neighbors. The result of this lack of nutrition was weakness and severe health damage up to death. Those who entered the infirmary never returned. Prisoners often suffered from diarrhea, so that neighbors feared a dysentery epidemic.

Poor work performance was also due to the disastrous undernourishment. Prisoners were granted a one-hour lunch break and ten minutes each for breakfast and supper, but these breaks usually failed because they had nothing to eat. For lunch, which usually consisted only of water and turnips, they had only about twenty minutes. Prisoners could barely walk upright from hunger; their eyes protruded, and their arms hung limply. They were incapable of work, and deaths were numerous.

Medical care in the camp

These conditions led to catastrophic health situations. The prisoners were physically and mentally at the end of their strength. Medical attention was urgently required. There were close connections between Elster GmbH and the camp. Two camp doctors, themselves prisoners, appealed to camp leader Wirker for better food, so that the health of the inmates would not be further endangered. Reportedly at the urging of Dr. Neste, potatoes were delivered – a one-time event in camp life. Dr. Neste intervened directly only once in medical matters. When reviewing the camp doctor's diagnosis because of epidemic danger, he saw the infirmary in the attic. Seeing the hall with the severely ill prisoners, doomed to die, made him aware of the continuous dying in the camp.

The worst of his duties was to co-sign the death certificates signed by camp leader Wirker and a French camp doctor. Neste signed up to twenty death certificates per day. The main causes of death listed were exhaustion, pneumonia, influenza, erysipelas epidemic (which could spread due to catastrophic malnutrition), emaciation and inadequate clothing, as well as intestinal diseases and bloody diarrhea caused by watery food and raw cabbage consumption.

Poison injections

Eyewitness Bahr reported that he served from 1941 to 1943 in the Neuengamme concentration camp. He testified under oath: 'At night, people were brought one by one into a designated room. There they were ordered to lie face down on the table. Then Brüning or I injected about 5 cc of phenol into the hole at the back of the head. They lost consciousness immediately and died one or two minutes later. Then Brüning and I carried them into the mortuary next door […]' The public prosecutor’s office assumed that Bahr might also have been active in Bautzen and Kamenz. Although this was not proven, it is considered quite likely that in Kamenz, too, unfit or sick prisoners were injected with poison by medical personnel, including by other inmates.

Severely ill prisoners were taken to a room in the attic; their bodies, wrapped in blankets, were carried to the cellar, where furnaces for burning corpses were located. Being sick in Kamenz was extremely dangerous. Everyone feared being 'taken upstairs' – that meant the end. One prisoner who suffered a nervous breakdown and screamed incessantly was 'taken upstairs' and never seen again.

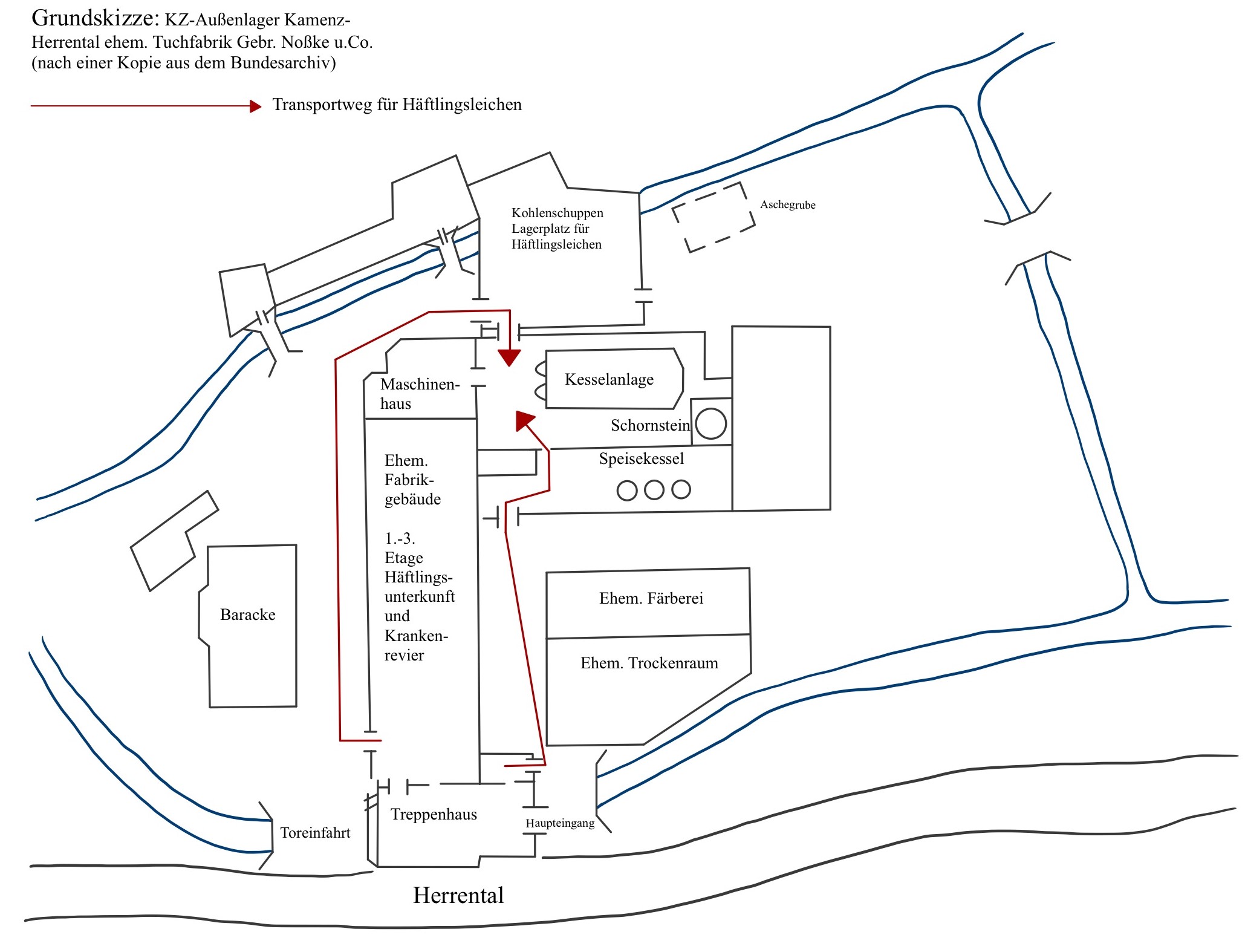

Disposal of the victims: cremation in the heating plant

Two prisoners employed at the glassworks were trained to operate the heating system for cremation. Already after the arrival of the first transport in 1944, a dead body was observed being carried to the boiler house. Only the feet of the covered corpse were visible, and smoke soon rose from the chimney. In the period that followed, the burning of prisoners became a daily occurrence. The dead were carried from the camp building on the north side, first through the coal shed to the boiler house.

After neighbors began asking questions, the bodies were taken along a route not visible from outside, across the cemetery, to the boiler room. To conceal the process further, an additional room seems to have been built between the kitchen and the boiler room. Through a trapdoor in the ceiling, bodies were now dropped down. Six prisoners were assigned to the cremation work, and it was ensured that none of them left the camp alive.